Snowflakes are amazing symmetrical crystals and a unique and fascinating phenomenon that originated from a speck in a cloud. Adults can encourage young scientists to explore hexagons and emphasize the six-pointed structure of a real snow crystal. Learn about snow crystals and find activities to teach geometry and patterns with snowflakes.

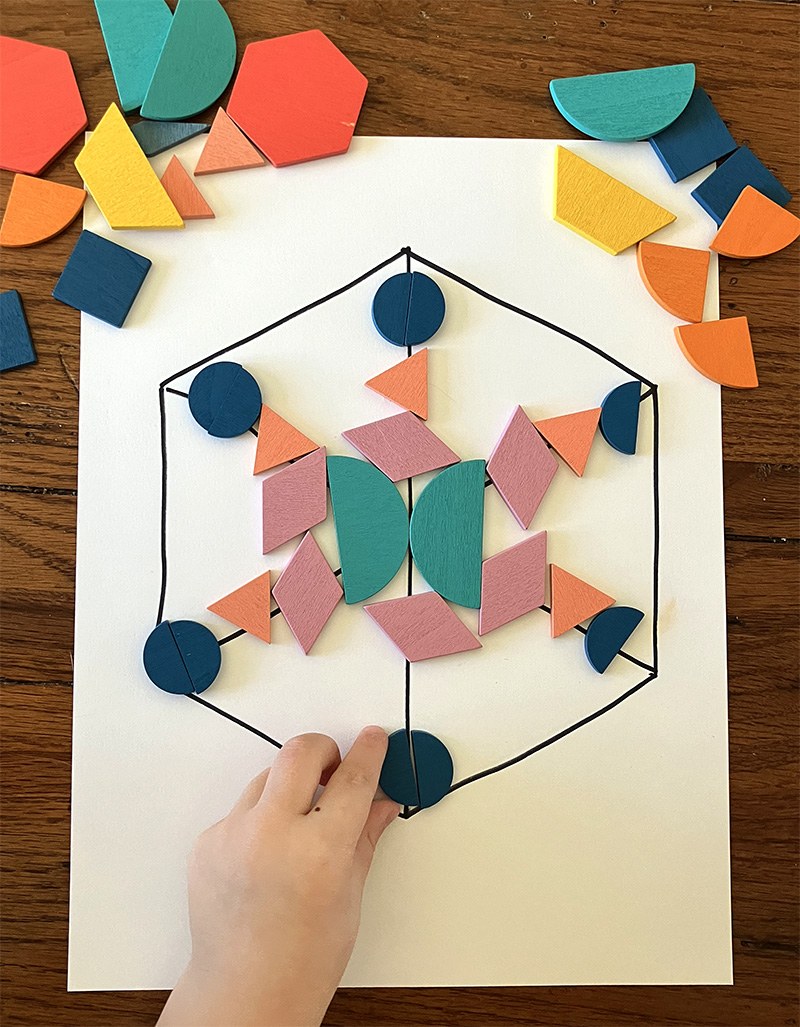

A child's hand places geometric shapes on a hexagon divided into six sections to create a six-sided symmetrical snowflake.

"A snow crystal is a letter from the sky." Ukichiro Nakaya, Japanese scientist (1900-1962) in Cassino, 2009

Snow science

A snow day is a great time to get outside and explore nature. Nancy Rosenow encourages early childhood educators to help children see the wonders of the natural world (Exchange, 2011). When it's snowing, help children wonder about snow! Most people have heard no two snowflakes are alike. "No two leaves, flowers, or people are exactly alike, either! Snow crystals are like us--we're each different, but we have a lot in common" (Cassino, 2009). However, in 1988 Nancy Knight, a scientist at the National Center for Atmosphere Research, found two identical examples while studying crystals from a storm in Wisconsin (Guinness World Records, n.d.). This is very rare. Typically, a snow crystal has six branches or dendrites and is shaped like a star, but some snow crystals form in plates or columns. Occasionally twin crystals form with twelve points as one six-sided crystal forms on top of another.

A snow crystal starts as a speck in a cloud. When a speck gets cold enough, water vapor sticks to it, and then layers of moisture form a six-sided crystal because water molecules attach themselves to each other in clusters of six. As they grow and become heavier, crystals fall from clouds to the ground at an average of three miles per hour. Once out of the cloud, the crystal stops growing. It may be damaged as it falls. Snow is not white, it's clear (Cassino, 2009).

Catch snow

Adults can encourage young scientists to catch snowflakes and study them. Even preschoolers can do this. Investigators need a dry, sturdy, dark piece of cardboard or foam core board. Place the board outside for at least 10 minutes before an attempt to catch snowflakes so that the board is chilled and the flakes won't melt on contact. Direct children to hold the board flat, gripping on one side, as the snow falls. Only catch a few flakes at a time to improve viewing. Use a magnifier to examine the crystals. Concentrate on the smallest bits on the board. They are the most likely opportunities to see defined crystals. If this doesn't work the first time, don't give up. The temperature has to be just right. If rain mixes at all with snow, it won’t work (Cassino, 2009).

Citizen scientist Snowflake Bentley

Wilson Bentley lived in Vermont from 1865 to 1931. From his childhood he was intrigued by nature and especially captivated by snowflakes. As a child, his mother gave him an old microscope to use. In 1885, he became the first person to capture a photograph of a single snow crystal using a microscope adapted to a bellows camera. In his lifetime he captured more than 5,000 photos (called photomicrographs) of snowflakes, no two alike. These images were then studied by scientists, artists, and fellow citizens (Guinness World Records, n.d.).

Exploring hexagons

Folding and cutting

Snowflakes are six-sided crystals (think of a pie cut in six pieces or a clock with hands at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12). Children can have geometry fun, learning to fold paper into six sections and cut their own paper snowflakes. Using this method, adults can emphasize the six-pointed structure of a real snow crystal rather than simply folding paper in a random fashion.

Children can cut the folded wedge any way they wish, but making cuts on only one side will create a more striking, six-sided shape when unfolded.

See Audodesk Instructables for detailed folding instructions: "Make a 6 Sided Snowflake."

Symmetry and patterns

Provide trays of geometric shapes and invite children to make snowflake designs. Start by placing objects on one of the lines, then repeat the pattern created on the other five lines to make a six-sided symmetrical snowflake. You can get creative with the items, but be cautious of choking and supervise children who still put objects in their mouths.

Potential objects: pattern blocks, tangrams, paper geometric shapes, buttons, beads, pom-poms, pouch caps, found objects from nature, glass gem rounds, geometric jewels, stickers, or bingo dabbers.

Download the Snow wonder PDF (includes a hexagon snowflake template)

For more winter activities, check out Outdoor play on winter days.

References

Cassino, M. (2009). The Story of Snow: The Science of Winter's Wonder. Chronicle Books.

Rosenow, N. (July/August, 2011). "Planning Intentionally for Children's Outdoor Environments: The Gift of Change." Exchange.

Snowflake Bentley. (n.d.). Wilson A. Bentley (1865-1931). https://snowflakebentley.com/ biography

Guinness World Records. (n.d.). First identical snow crystals. http://www. guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/ first-indentical-snow-crystals

Martin, J. B. (1998). Snowflake Bentley. Houghton Mifflin.