Posted: November 10, 2022

This article focuses on the intersection between community engagement, environmental justice, and educational outreach. Michelle Niedermeier's work over more than twenty years has focused on engaging with communities around environmental health and reducing disparities. She describes her work with the Pennsylvania Sea Grant (PASG) on Environmental Literacy and Workforce Development, and how that relates to her previous work with Pennsylvania Integrated Pest Management (PA-IPM).

by Kendall Van Son and Justine Lindemann

Sea Grant is a national program comprised of 34 locations housed at Universities across the United States, including several Land Grant Universities, and can be found in every Great Lakes and coastal state including Puerto Rico and Guam. Sea Grant program focus areas include Healthy Coastal Ecosystems, Resilient Communities and Economies, Environmental Literacy and Workforce Development, and Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture. The Pennsylvania Sea Grant program (PASG) works in both fresh and marine watersheds including Lake Erie, the Susquehanna River (leading into the Chesapeake Bay), and the Delaware River Estuary. Sea Grant’s functional areas focus on research, extension, communication, and education.

Michelle Niedermeier has been in the role of Education Lead with PASG since July of 2021 and is working to support already-existing programs (e.g. K-12 educator professional development and GIS-based experiential learning programs) and to innovate new programs. Before working for the Pennsylvania Sea Grant, Niedermeier worked with the Pennsylvania Integrated Pest Management (PA-IPM) which is housed in Penn State’s department of Entomology. As program coordinator and educator in PA-IPM’s Philadelphia office, she focused on reducing pest-related health disparities in lower income neighborhoods. As a part of Sea Grant, she continues to focus on educational programming that reduces health disparities and builds resilience in coastal communities.

Of the four issues of focus mentioned above, Niedermeier is responsible for the Environmental Literacy and Workforce Development education. For example, she works with the Center for Great Lakes Literacy (CGLL) on outreach to teachers on environmental justice. Educational programming must align with both Sea Grant and CGLL priorities in the Lake Erie watershed, but according to Niedermeier, “it’s pretty easy to draw the lines between some of these principles and environmental justice and social issues.”

She outlines an expansive educational agenda: “We’re focused on things […] like invasive species and native species […] but we're also talking about watershed fish and public health, and talking about how many fish from the Great Lakes should you eat? What are the health implications? We're talking about pollution and marine debris, and we're talking about traditional ecological knowledge.”

An ongoing educational opportunity that focuses on reducing health disparities across PA is the Meaningful Watershed Educational Experiences (MWEE). This place-based experiential education is student driven and teacher guided. The experience culminates in an action project of the students’ choosing. The MWEE program lends itself to justice issues by giving students a voice and power to change something in their community. Student empowerment comes from the process and the outcomes: "We're going to learn all this together. We're going to use data. Data is going to drive it. You have to have arguments (that are) supported by data. You have to inquire; you have to reach out; and then we need to do something that makes a change." MWEE programs help students to connect environmental and public health issues by showing how nature can impact well-being, making it a vital experience for all students.

The MWEEs also focus on reducing disparities by trying to increase the number of schools where this type of education is available. Under the Chesapeake Bay watershed agreement, all PA students in kindergarten through 12th grade are supposed to have MWEE experiences in elementary, middle, and high school. Many times, however, this does not happen. Niedermeier remarked that while schools and districts across the Commonwealth, including in Philadelphia, recognize the importance of the MWEE, opportunities are limited (whether from funding, access to outdoor spaces, or from safety concerns) and it is often omitted. In urban areas such as Philadelphia, it can be even more complicated. With just under 200,000 students and over 200 district-operated buildings, other issues often take priority. “Environmental literacy and getting kids outdoors can get lost in the curriculum, but it is easy to connect the dots between the environmental and public health and connect these to nature and personal wellbeing. So, this is one of those things where I'm networking and building partnerships to help remove the barriers to success.”

Through previous environmental justice work with PA-IPM from 2000-2021 in Philadelphia, she built relationships with people and groups across Philadelphia that can benefit from Sea Grant programming as much as they did from her IPM work. She highlights the connections between many of the focus issues, commenting that “Sea Grant and climate-change go hand in hand.” Her approach to building relationships for her environmental justice IPM work in Philadelphia mirrors the way that she is working to expand access to Sea Grant programming across Pennsylvania. She sums it up perfectly: “I would sit back and just […] listen to what folks had to say and just keep showing up. Because I think that's what’s really important – to listen, to be consistent about showing up and then to kind of explain how you fit in. Some people got it right away. Some people still 17 years later are probably like, "I don't know that Michelle girl, she is nuts."

For both projects she has been involved with, the work is much larger than a single issue. Listening to residents, involving youth and teachers in programming and program development, and helping people to understand not only the complexity of an issue (whether it is watershed health or integrated pest management) but also their role in finding and building solutions to that issue is central to building community capacity and collective resilience.

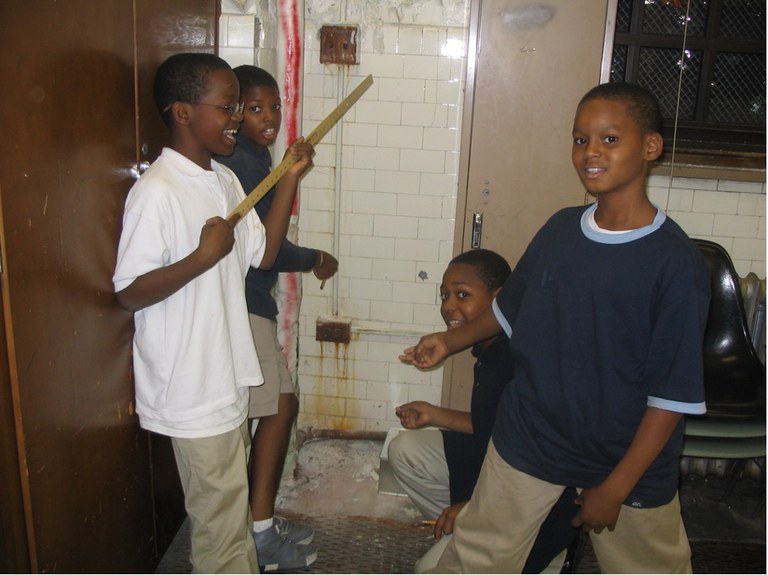

A quick example by way of conclusion: in an older school building in Philadelphia, a radiator steam pipe had burst and water was collecting everywhere. “There were cockroaches and there was mouse poop. It was a disgusting classroom. So the kids said, ‘We think we can get this fixed.’ I said, ‘All right.’ Like, ‘What do we need to do?’ We strategized; we came up with things. The kids wrote a letter. I wrote a letter from the PA-IPM program. We sent it to the school district. We let the principal know we were doing this. That pipe and that window were fixed the next week.”

Collaboration among middle school students, facilitated by an outside expert, catalyzed immediate action by the school district. “Now this is just one little thing. […] But those kids saw change because of their voice.”

If you would like to receive The Urban Resilience Report in your inbox, please click here to join the listserv.

If you would like to receive The Urban Resilience Report in your inbox, please click here to join the listserv.